Case 1

Yoshinobu Nishizaki: A warning bell for the times, entrusted to a black iron warship

What if ships flew in the sky? This is how the idea behind Space Battleship Yamato is always explained. The reality, however, is a bit more complicated.

After Triton of the Sea (1972), and Wansa-kun (1973) Producer Yoshinobu Nishizaki, who had worked on anime based on Osamu Tezuka’s works, wanted to make a science-fiction film for his next project.

He approached his old friend Keisuke Fujikawa, who had also worked on Wansa-kun and had made a big hit with his scripts for Mazinger Z (1972). Nishizaki’s first idea was to hold a symposium with science-fiction commentators and use the ideas that came out of it as the basis for a new program. He asked several commentators to submit ideas, but none of them were to his liking. It was the same for Fujikawa. Then the two of them discussed the project together.

Nishizaki said he wanted to do something using warships. Fujikawa felt that a warship would not give a sense of speed and suggested, “If we’re going to use a warship, we should come up with an idea that makes it fly.” Nishizaki agreed, saying, “Let’s do that.” This was the start of the Yamato project.

(Keisuke Fujikawa, The Birth of Anime and Tokusatsu Heroes, Nesco, 1998)

Why did Nishizaki want to make a warship film? One reason may be that he had in mind the novels of Juza Unno, Haruno Oshikawa’s “Undersea Warship” series, and other bloodcurdling adventures. Another reason is clearly stated in the proposal.

We designed our “warship” like a “rock mass.” Space ships in science-fiction are usually metallic and streamlined. It has been a symbolic form of the era of economic growth that has stimulated people’s sense of beauty. However, something like the “steam locomotive boom” also occurred here. Heavy, slow, and cumbersome steam locomotives, the complete opposite of light, streamlined cars, have suddenly become very popular. Perhaps people found in the form of steam locomotives a “humanity” that they tended to forget during the era of economic growth. This has become a social trend and is changing people’s sense of beauty.

(Yamato Perfect Manual 2, Tokuma Shoten, 1983)

The proposal quoted above was the third in the Yamato production process, so let’s call it the third Yamato proposal. This applies not only to the design, but also the overall concept for the work. It is a revival of something that was forgotten due to economic growth. When we take a broad look, we realize this is not a hidden flavor, but rather a theme that is taken up throughout the entire story.

Nishizaki worked as a music producer before joining Osamu Tezuka’s Mushi Pro studio. There, he was in charge of sales and marketing and made a name for himself. At the same time, he established Office Academy and served as its representative. Triton of the Sea was also produced by him (under the name of Animation Staff Room). He also planned Wansa-kun as a board member of Zuitaka Enterprises (now Zuiyo). Like Triton, it was based on an original story by Osamu Tezuka, but Mushi Pro treated it as a production. Nishizaki was involved in the management of Mushi Pro at the time, but the company went bankrupt just prior to the broadcast.

The Yamato project was to be produced under Zuitaka Enterprises, but another of this company’s projects, Girl of the Alps Heidi, was to be aired in the same time slot. It was not good for a single company to produce two overlapping programs in the same time slot, so production shifted to Nishizaki’s Office Academy.

(Koyo Ono, Shigeto Takahashi Talks About the Early Days of TV Commercials and TV Anime in Japan, Kyoto Seika University Bulletin, No. 26)

The Yamato project (not named Yamato at first) was created by Nishizaki, Fujikawa, and Eiichi Yamamoto, a scriptwriter he had known during his Mushi Pro days, as well as Aritsune Toyota, a science-fiction writer who had worked on many anime scripts. These were the initial members who formed the core of the project.

However, since it was the first full-fledged SF anime in Japan, many had a hard time understanding it. The following is Toyota’s impression of Nishizaki’s presentation to the TV station:

“The station’s response was terrible. ‘How could there be a story about Earth falling to ruin?’ ‘It’s not set in space, is it?’ It was a sloppy response, and they rejected it at once.”

(Aritsune Toyota, Genesis of Japanese SF Anime, [above left] TBS Britannica, 2000.)

In addition, there were other comments such as:

“No monsters?”

“I think it’s better to make it a robot story.”

“It’s too belligerent, and I’m afraid of criticism.”

(Aritsune Toyota, You Can’t Become a Science-fiction Author, [above right] Tokuma Shoten, 1979)

However, Nishizaki’s innate tenacity enabled him to successfully complete the project later.

His original idea for Yamato was based on Robert A. Heinlein’s Methusulah’s Children (1958). At that time, it was a science-fiction novel that had been translated [to Japanese] in 1963 under the title Escape from Earth. The story is about Lazarus Long, elder of a long-lived race of people. In order to avoid persecution on Earth, they set out on a journey to another star system in a spaceship named New Frontier in search of a new home. The story is relatively simple in structure, but is full of surprising encounters with a variety of alien civilizations. It is excellent entertainment. The original form of Yamato can be seen in this journey into the unknown.

Nishizaki’s sense of crisis over economic growth takes the form of environmental pollution caused by radioactivity as the plot of the story. This seems to have been Aritsune Toyota’s idea. The story reflects the pollution of the world at that time.

Case 1.2

Yoshinobu Nishizaki: Changing the name to Yamato due to momentum

The first project was titled Space Battleship Cosmo (tentative title). Keisuke Fujikawa prepared a proposal under this title in late April 1973 and submitted it to the agency. It seems to have been a temporary proposal to advance the project. This was the first Fujikawa/Yamato plan.

A thousand years in the future, Earth has been contaminated by a mysterious attack from space. A space battleship sets out in search of a second Earth for emigration.

Concept art for Rajendoran spaceships, Kenichi Matsuzaki

In parallel with Fujikawa’s proposal, Aritsune Toyota also prepared a proposal. Let’s call this the second Yamato proposal. The title was Asteroid 6. Some say it is called “Ship” instead of “Six,” but since it is clearly stated that way in Toyota’s book, I will use this name.

The story takes place at the beginning of the 21st century, when Earth is attacked by a nuclear missile from the Rajendora aliens. Earth is enveloped in radiation, and is only one year away from extinction. However, it is discovered that the planet Iscandar has a radiation removal device. They hollow out the asteroid Icarus and build the Asteroid Ship Icarus, which will travel to Iscandar. The basic structure of the story is already established here.

At the end of the story, the Rajendora aliens are actually already dead. The story reveals that the remaining giant computer invaded Earth with a robotic fleet (no clear description, but presumably so) to transplant a single remaining vine. When the crew of the Icarus learns of this and tramples the vine, the computer loses the object it is supposed to protect and self-destructs (a kind of runaway). At this time, Iscandar is located in star system at the center of the galaxy, at a distance of 20,000 light-years.

The crew was perfectly multinational, consisting of Germans, French, Japanese, an African (named Muginga, indicated as “black”), Soviet, Thai, Hungarian, Chinese, etc. There are also many female characters. The image of Icarus was based on Mikasa, the flagship of the Japanese fleet during the Russo-Japanese War, and was designed by Kenichi Matsuzaki of Studio Nue. The shape of the ship changed as it was repeatedly modified.

One of the staff members said, “What’s this? It looks like Nagato.”

Nagato was the flagship of the Allied Fleet of the former Japanese army before the Yamato. But Nagato was not well known, so Yamato was chosen. Thus was born the name Space Battleship Yamato.

(Gundam Mono: The Men Who Made Gundam, Kodansha, 2002)

The third Yamato project proposal was then completed. The theme of the story was written in the proposal as follows:

Now, as to whether or not we can break through this impasse, history has proven that it is possible. Human civilization has been in crisis many times, but each time we have escaped, and we are here today. The important thing is that we should not define ourselves as cogs in a dehumanized industrial organization. We are “human beings” in a different dimension from things.

We have planned Space Battleship Yamato in the hope that it will speak to children in particular, as well as adults, about this awareness and dreams that we as human beings must have now more than ever. It is a science-fiction adventure action drama that tells the story of a boy and a girl who stand up against the threat of extinction of all mankind on Earth in the year 20XX.

(Yamato Perfect Manual 2, Tokuma Shoten, 1983)

The “mission to save the Earth” is clearly stated here as the main idea of the story, and the rugged, tactile steel battleship was intentionally used as a visual motif, a symbol of the humanity that saves the Earth.

The basic streamlined sense of science-fiction is utilized, while at the same time adding the rugged element of a rock mass that is far removed from the refinement of an black iron warship. It is a design that shows the presence of man in space. It will not fail to appeal to children.”

Incidentally, according to Yamato copyright trial materials prepared by the Ministry of Justice (Case No. 20820 for an injunction against copyright infringement, 1999 and Case No. 14077 of 2000, a counterclaim for confirmation of moral rights), the proposal was prepared around March 1974.

However, the same proposal states, “This year, an America movie called The Poseidon Adventure was a big hit.” So it would be reasonable to assume that the proposal was prepared in 1973, the year that movie was released in Japan. Or was that part only written in the first phase and remained uncorrected?

In the third proposal, the name of the battleship was changed to Yamato. The shape of the battleship is the same as in the second proposal by Toyota. It is two kilometers long, one kilometer wide, and 500 meters high. The final form of Yamato is 265.8 meters in length, so it was to be much larger. (Incidentally, the Battleship Yamato was 263 meters in length.)

This size is for the one attached to bedrock as a defense while in flight. In battle, the bedrock is blown away and a steel spaceship appears. The scattered bedrock also serves as a defensive screen in the form of a ring. This concept was later used for Shiro Sanada’s asteroid ring.

In the third proposal, all crew members are changed to Japanese. The main character is a brave warrior named Shinobu Kotake. He is an elite with extensive scientific knowledge because he is infused with the memories of many scientists through the RNA factor (famous for its memory experiments on mice). The Rajendora aliens have been converted into a real life form.

Yamato‘s chain of command is split between Admiral Hayato Kenmochi and Captain Katsuhiko Izumi. (In the final form, the captain and commanders are combined.) A large-scale crew mutiny was also planned. This differs from the almost monolithic final form. (However, a mutiny by Sanada was planned in the final form, but it disappeared and the scriptwriter made a mistake in foreshadowing it.) Analyzer and Yoshikazu Aihara of the communication team appeared at this stage.

Yamato loses crew members one after another in the battle against the Rajendora. They receive the radioactivity removal device at Iscandar and return home. After the final battle on the planet Rajendora, only Kotake and Aihara are left as crew members. (Analyzer is “executed” for stealing something on Iscandar.)

The heroine was Machiko Kami (based on singer/actor Megumi Maoka), but during the final battle, she activates the radiation-removal device to exploit the weakness of the Rajendora aliens, who could not live in an atmosphere without radiation. However, due to an operational flaw, she dies. Finally, a wounded Aihara dies when Yamato lands in Earth’s ocean, and Kotake is the only survivor.

If this plan had been realized, it would have been fundamentally different from Yamato as we know it.

The basic line of the story, including a social crisis reflecting the current state of environmental pollution, a sense of mission to save the Earth, and an adventure through space, was already completed at the stage of the third Yamato proposal.

Concept art for a matter transmitter, Kazuaki Saito

On the other hand, there were many differences.

The “passion” of sympathy, friendship, etc. between men who fight, such as Juuzo Okita and Mamoru Kodai, or Domel, is not seen. The story is a school-like portrayal of a group of young men, the passionate but sometimes dark emotions of Susumu Kodai, and the sensitive, arrogant, and sometimes insane personality of Dessler. No human drama is seen at this stage. In other words, there were only superficial similarities to the Yamato we know.

The proposal shows that Nishizaki was a creator-oriented producer who put his own message into his work. (Eiichi Yamamoto was the one who compiled the proposal in the end.) Because he was an independent producer, his work has a strong message. This was also why he was able to take reckless actions, such as making a movie without regard for profitability, unbound by the logic of a company.

The “Did it My Way” producers were the ones who created the breakthrough for the anime boom that came later. Or it could be said that they promoted its birth.

However, he was not satisfied with the third Yamato proposal. That is why he sought a new catalyst.

Case 2

Leiji Matsumoto: Not a war story, but a great voyage in space

The Yamato at the stage of the third proposal was an evolution of the battleship Mikasa. It was a sleek, streamlined shape rather than a clunky one. This was not satisfactory for Yoshinobu Nishizaki, who was looking for a rugged texture.

At that time, Leiji Matsumoto joined the staff at the recommendation of Yoshihiro Nozaki, the design producer. His role would be to design the characters and mecha, and to direct. There was an earlier candidate (Keiji Yoshitani), but he was turned down. The main art designer had not yet been selected. According to Matsumoto, he was later approached by Bouken Oh (Adventure King) magazine (published by Akita Shoten) to create a manga serialization.

(Leiji Matsumoto, From the Far Place Where the Ring of Time is Linked, Tokyo Shoseki, 2002)

At this time, the direction of Matsumoto’s works was divided into three parts: his battlefield manga set in World War I and II, SF works such as The Fourth Dimensional World and Sexaroid, and the “4.5 tatami mat” series which depicted the daily life of young men with no prospects for advancement, such as in Otoko Oidon.

He is a rare artist who has both a very long bird’s-eye view, as if he were depicting even the history of the universe in a single frame, and a microscopic perspective, as represented by the ramen, rice and bread of everyday life. The main characteristic of his style is the blend of poetic sentiment and a subtle balance of carelessness, which is rare in science-fiction manga, where inorganic taste is the norm.

Matsumoto always had a strong desire to create anime, including his personal attempts to research anime production. However, when he was first approached about Yamato, he thought to himself, “Why start with Yamato of all places?”

(Farewell to Yamato Fixed Data Materials Collection, Studio DNA, 2001)

This was because of the weight of historical reality embodied by the battleship Yamato.

“It was painful just to imagine what the bereaved families in their living room and in other countries would feel when they see the story of the Battleship Yamato. I put the idea together with the conviction that Yamato should not be just a war drama, but also a “lyrical tale of a great voyage in the ocean of space.”

(Leiji Matsumoto, From the Far Place Where the Ring of Time is Linked, Tokyo Shoseki, 2002).

He had always enjoyed the joyful animation of Fleischer’s Mr. Grasshopper Goes to Town, which combined poetic sentiment with a childlike spirit. However, the 1975 TV anime adaptation of Maya the Honeybee was disappointing for him. He later recalled, “I was happy with Yamato, but I would have been very excited if they had asked me to do Maya.”

(Fantoche magazine, Vol. 2, 1976).

Matsumoto’s SF stories are limited to the past or the future, and in many cases, they are depicted from the characters’ viewpoint and a bird’s eye view that transcends good or evil. If they dealt with the former battleship Yamato head-on, it would be purely Japanese, not SF with a bird’s eye view, making the leap very difficult. He may have hesitated because of the expected difference in style from his own work.

When Matsumoto met Nishizaki, the famous image of the rusty red Yamato lying on the reddish-brown ground was immediately created. It was the first image that approached the core of Nishizaki’s idea of the black iron warship. As is well known, it appeared in flesh and blood form through Matsumoto’s outstanding visualizing skills. Paradoxically, because this Yamato design was a weapon, it became the seedbed from which the blood of drama was born.

Incidentally, President Shigeto Takahashi of Zuiko Enterprises, the original planner of the Yamato project, also played a role in the birth of Yamato.

“After several people refused, Leiji Matsumoto drew the character, and the decision was made. At first, he drew something that looked like a sailing ship, named Musashi, and there were many others. In the course of chatting with him, he asked, “What if we fly a battleship?” I remember saying to him, “Yamato is still very much in the Japanese people’s memories.”

(Koyo Ono, Shigeto Takahashi Talks About the Early Days of TV Commercials and TV Anime in Japan, Kyoto Seika University Bulletin, No. 26)

Leiji Matsumoto’s Night on the Galactic Railroad from Yamabiko

No. 13 (Kyosotengaisha, 1979). This was an homage to Kenji

Miyazawa’s Night on the Galactic Railroad.

Other artist’s visualizations pale by comparison.

We do not know how much of a role Takahashi’s advice played in Nishizaki’s work. The name and form of Yamato were not the result of one person’s consciousness. Rather, it seems that the name and appearance of Yamato resulted from the collective work of several minds in the process of planning the project.

Case 2.2

Leiji Matsumoto: tragedy does not suit fantasy

In 1971, Leiji Matsumoto created his own version of Night on the Galactic Railroad by Kenji Miyazawa (circa 1924 ~ 1931). It was a fantasy story in which a boy with an uncertain future reads Night on the Galactic Railroad and expands the wings of his imagination. The image of a train (steam locomotive) traveling along the Milky Way is depicted in the story, which later became the basis for Galaxy Express 999. This work may have been one of the reasons Matsumoto was chosen for Yamato.

Matsumoto transformed and fleshed out the project created by Yoshinobu Nishizaki, Keisuke Fujikawa, and Eiichi Yamamoto. It was Matsumoto who changed the distance of Iscandar from 20,000 light-years to 148,000 light-years. This was because “the distance was too short” for the drama.

(Farewell to Yamato Fixed Data Materials Collection, Studio DNA, 2001)

The distance between Earth and the Large Magellanic Galaxy is actually a little farther, 157,000 light-years. However, after consulting with astronomers, Matsumoto decided to go with the smaller number.

He created a cosmic map as a bird’s-eye view of the universe. Along with the story structure, he created a detailed route schedule. Even in space SF, though encounters with alien planets were clearly depicted, the navigational part of the process was surprisingly never given much importance. However, Matsumoto’s meticulous composition gave Yamato a clear outline as the story of a space voyage rather than a war story.

It is to Matsumoto’s credit that Yamato has the framework of a human drama. In the third Yamato proposal, the tone was hard and gloomy, with all the crew members except the main character dying. However, with his participation, the tone changed drastically.

Or, because the battleship Yamato itself was used as the visual motif, the dark tone that hints at historical fact may have been avoided. The direction proposed by Matsumoto was to return to the starting line of Heinlein’s Methuselah’s Children, the lively space adventure that gave Nishizaki his motif.

With Matsumoto’s participation, the names of the characters were also cleaned up. The crew members were named after characters from period dramas and children’s stories. Juuzo Okita was named after Soji Okita (of the Shinsengumi) and Juzo Unno (adventure novelist). Shiro Sanada was named after Yukimura Sanada of The Ten Warriors. Hikozaemon Tokugawa was from the Tokugawa family + Hikozaemon Okubo (famous for his opinionated views during the reign of Shogun Tokugawa Iemitsu), and so on. Matsumoto’s intention in using names of the Shinsengumi was also to structure the story as an ensemble drama.

The rough designs drawn by Matsumoto were cleaned up by Nobuhiro Okasako. In truth, many of his rough designs for Daisuke Shima, Shiro Sanada, and others do not retain much of their original form. However, Matsumoto’s concepts have a unique taste and gave life to Yamato. In particular, Nishizaki fell in love with his mystical female images (he was not a big fan of male images). Thus, Starsha became a trademark of the work.

Sakezo Sado’s design fully retained Matsumoto’s taste. As the name implies (named after a sake brewery), he’s a drinker with a stylish personality. Scenes of him drinking sake give a unique texture to the SF taste of the story. His presence decisively changed the originally tragic story. We can also see in Susumu Kodai’s sometimes introverted character the typical juvenile image of Matsumoto’s works.

Matsumoto was the first to bring the idea of mecha design to anime. The design of the Earth Defense Forces’ spaceships, which were defeated and destroyed by Gamilas, was an extension of modern science. Mamoru Kodai’s ship, Yukikaze, is reminiscent of the space shuttle, which did not yet exist at that time.

On the other hand, Yamato, a symbol of Earth’s rebirth, cleverly incorporates the essence of the old battleship Yamato, and there is a disconnect in the design concept. Visually, it is clear that a “leap” has been taken in the story.

The Gamilas space fleet is different from both the Earth Defense Fleet and Yamato in terms of silhouette, detail, and everything else. The same is true of Iscandar. Each alien civilization has different technology and culture, so their design ideas are naturally different. The creation of three visually different alien civilizations made this clear.

And in an age when many people felt a sense of entrapment, the work made us dream of a different society as “utopia.” It was only with the outstanding talent of Leiji Matsumoto that this idea was realized.

Case 3

Keisuke Fujikawa: Criticism of the times in the main character

“I felt like rebelling against the times.”

This was how Keisuke Fujikawa, screenwriter, described his thoughts on Space Battleship Yamato.

(Keisuke Fujikawa, The Birth of Anime and Tokusatsu Heroes, Nesco, 1998)

Before anime, Fujikawa had already worked on tokusatsu films such as Ultraman and Ultra Seven. I mentioned in Chapter 1 that these two were “experimental” in their storytelling, and it was the same with him.

For example, in Ultra Seven Episode 16, Eye in the Darkness, the rock alien Annon (shown at left) attacks the rocket sent by Earth to his home planet, deeming it an act of aggression. This is a misunderstanding, but it is also relative to the Earth viewpoint. In the end, Annon accepts persuasion through a battle and returns to his home planet. This episode also adds a flower to the Ultra series, in which justice can be reversed depending on one’s position.

Before Yamato, Fujikawa’s biggest hit anime was Mazinger Z (1972). He brilliantly adapted Go Nagai’s original manga and paved the way for later robot anime. On the other hand, he also developed the motif that justice is not necessarily universal.

Fujikawa was in charge of Episode 7, Baron Ashura’s Plot, in which a city is ravaged by battle and the citizens mistakenly believe that the Photon Power Institute is the cause. Koji Kabuto, accused of the crime, is troubled about the justice for which he stands.

He was also in charge of Episode 17, Underground Mechanical Beast Horzon V3, in which Doctor Hell causes a major Earthquake and offers to save the Photon Power Institute if they surrender. The citizens take advantage of the situation and force the government to meet their demands. Such episodes can be seen as depicting the “stupidity” of the citizens. But they also show that justice was not always obvious and simple at that time.

At the time, “TV manga” was a synonym for “vulgarity” among sensible adults. However, there was a desire to create a new form of expression. After collaborating with Yoshinobu Nishizaki on Wansa-kun, Fujikawa also participated in Yamato.

As mentioned earlier, Yamato started out as a symposium with science-fiction commentators. At the time, it was common practice to simply find a popular manga and adapt it as the basis for a film (with the exception of Tatsunoko productions). Fujikawa was strongly impressed by Nishizaki’s attitude of creating something new from scratch.

He created the first Yamato proposal titled Space Battleship Cosmo, in which, as we have seen, Earth was contaminated by radioactivity. Humans have migrated to an underground city, and the situation has continued for quite a long time. The underground city is controlled by an organic computer. The human race enjoys a temporary peace of mind in the city, but as radiation gradually permeates the underground, they make a great exodus in search of a new planet for emigration.

The theme of the story is an exodus from a controlled society in the form of a computer. Fujikawa’s critique of the times is contained in this theme.

“Economic growth has been losing its momentum, and at the same time, people who rejected authority, hated restraints, and disliked a sense of mission, and had lived their lives in a freewheeling manner, were finding it difficult to do so. Those who had lived comfortably up to that point could not keep up with it, and some started to drop out. People who had been living under strict control in a cramped and stifling salaryman society needed to vent their pent-up frustrations. They must have sought roman[ce] in a magnificent cosmic setting to release their stress. By capturing the atmosphere of the times, we responded to the needs of those times.”

(Keisuke Fujikawa, The Birth of Anime and Tokusatsu Heroes, Nesco, 1998)

This trend was common not only in Japan but also in other developed countries. The need to grasp all information led to a shift from an industrial society to an information society, where the entire society is under the fetters of control.

Fujikawa’s escape from the computer-controlled society turned into a space voyage to Iscandar. His desire to escape from the sense of entrapment was condensed in Yamato‘s voyage itself and in the main character, Susumu Kodai. At that time, in order to play the role of a hero, the protagonist of an action story had to be completely flawless, sometimes robotically lacking personality. The average protagonist of a story could be replaced by a character from a different story without much discomfort. In such an era, Susumu Kodai was clearly out of the norm.

According to Fujikawa, somes fans called him, “the anti-hero of the century.” Susumu Kodai was a hot-blooded man who made many rash mistakes. He is often described as shortsighted and flawed. However, with the help of intelligent and calm individuals such as Daisuke Shima and Shiro Sanada, Kodai became a more relatable figure and the story was enriched.

Susumu Kodai is not a shallow character. He has the trauma of losing both parents in the war and sometimes withdraws to be alone. When a Gamilas soldier is captured, Kodai lunges for him with a knife, a reaction to his own trauma. However, when he realizes that his opponent is a human being with blood in his veins, he does not hide his sympathy for his enemy, either. He is a lovable character with complicated circumstances and a childish side. That is Susumu Kodai.

He is the most volatile character and the one who reveals his true emotions, whether positive or negative. The amplitude of Susumu Kodai’s emotions is so great that Fujikawa may have intended him to be the antithesis against the tendency to suppress everything and be swallowed up by a controlled society.

Incidentally, Fujikawa also offered ideas based on his experience working on action stories. A mirror is launched into satellite orbit to reflect laser beams, a reflection satellite gun that covers blind spots. Later, the same idea was proposed in the Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI), which attracted a lot of attention. The idea was to shoot down intercontinental ballistic missiles by reflecting laser beams off satellites, the same as a reflection satellite system.

This idea was originally used in Mazinger Z to fight flying monsters. In Episode 19, Flying Demonic Beast Devil X!, instead of using the rocket punch to attack a flying opponent in a straight line, which can be dodged, it arcs around to hit the enemy from behind. In other words, it attacks from a blind spot. The idea is said to have its origin in Fujikawa’s script for the TV drama Me and a Siamese Cat (1969), in which the hero hits a rock with a bullet and uses the ricochet to defeat an enemy at an angle that would normally be impossible.

[Translator’s note: the Japanese Wikipedia page describes Me and a Siamese Cat thusly: Jiro Neida, a young man who used to be a lawyer, and his three young daughters run a clothing store in order to quit being thieves and rehabilitate themselves. They confront social evils. This entertainment work interweaves sex appeal, action, comedy, etc.]Case 4

Toshio Masuda: Susumu Kodai’s roots are Yujiro Ishihara?

Toshio Masuda, a film director famous for Hill 203 and Tora Tora Tora! also participated in Space Battleship Yamato as a supervisor. He wasn’t the first director to transition from live-action to anime; Seijun Suzuki had joined Lupin III (TV series 2) as a supervisor. This was apparently one of the helping hands he received from others after being laid off due to the unpopularity of Branded to Kill. Even today, it would be unusual for a busy, front-line director to be in charge of anime composition.

At the beginning of the project, Yoshinobu Nishizaki offered Masuda the role of story development, script, and directing. However, after attending three planning meetings and expressing his opinions, he was forced to leave the project to work on a movie. His initial involvement ended there, but what he emphasized at the planning meeting for Yamato was realism.

“I said at the beginning that I didn’t want a manga-like picture. I wanted him to depict fighter planes and battleships like in a realistic movie. It was all about pushing them to be real.”

(Toshiaki Sato and Mamoru Taka (eds.), Toshio Masuda, Film Director, Ultra Vibe, 2007)

This realism line is consistent with the direction taken in Lupin III and Gatchaman. With the eyes of a first-rate director, he identified what had been lacking in anime up to that point, and what was necessary for anime in the future. On the other hand, he was also fascinated by the expression of the anime genre.

“Well, what was so interesting about my first anime project? First of all, even though we are in the same film industry, the anime world has different ideas. In other words, there are a lot of restrictions in the film industry. The performance of actors, the issue of pay, schedule, and so on. Inevitably, the image is suppressed and becomes regressive. This is the reason why Japanese films have been going down the drain. So, in that sense, anime is free. The stage allows you leap at will, and nothing is impossible. Nothing could make me happier.”

(Kinejun, September 15, 1978).

Masuda got involved in the production of Yamato not only because of its potential for animated expression, but also because of his own qualities. He is sometimes regarded as “right wing” due to his war movie image with Hill 203, The Empire of Japan, and Tora Tora Tora! but a closer look at these films reveals many superficial assumptions.

Shunsuke Tsurumi once praised Mitsuru Yoshida, the author of The Last Days of the Battleship Yamato (1952), for “keeping his image of the war in the expectation dimension,” not in the retrospective dimension. The “retrospective dimension” is a perspective that looks back on the past from the present, while the “expectation dimension” looks at the future from the present. If history is judged solely from the perspective of current values, it is difficult to see the truth. It is also difficult to generate motivation for change.

The film Hill 203 (1980) vividly depicts the Russo-Japanese War, from the Meiji Emperor at the top of the ruling class to ordinary people on the street. The reason for the lack of overt anti-war sentiments is said to be based on the public mood of the time, when there was not much opposition to the war. A young officer with a love of Russian literature is transformed by the madness of war. The scene in which he calls General Nogi, who is trying to be a conscientious man, a hypocrite for his hubris, is a masterpiece.

Through his war films, Masuda portrayed human beings swept away by war in the great torrent of Japanese modernity. On the other hand, he also depicts people resisting to gain the freedom of their souls in the great prison of modernity.

He was known as the master director of Nikkatsu action films. Yujiro Ishihara was the top star for Nikkatsu Studio, making his debut in a film version of his older brother Shintaro Ishihara’s work. (Shintaro Ishihara also proposed the original idea for Yamato Resurrection.) He played a young man who lost his soul and ran amok in the postwar consumer society, and became a darling of the times.

In The Red Wharf (1958), Masuda set the story in Kobe, a stateless city in Japan, and Yujiro played an outlaw with a “yearning to escape.” The film is said to be an adaptation of Jean Gabin’s Mochigo, set in the Algerian Kasbah. That film is about a young idealistic scholar who is crushed when he tries to denounce the damage to his crops caused by rainfall from Chinese nuclear tests (!). Masuda’s shots of the streets of Kobe, reminiscent of Asia and North Africa, not Japan, left a lasting impression.

In Zero-sen Kurokumo Ichika (1962), Yujiro plays a gritty soldier who is unable to make the most of his ambition in the face of the great obstacles of the military and war.

In Escape to the Sun (1963), Yujiro plays a man who abandons his nationality to be crushed by the military industry that still thrives in a peaceful nation.

In The Life of the Showa Era (1968), he plays a former terrorist who questions his nationalistic aspirations and finds the meaning of life on the other side of the world.

Masuda entrusted Yujiro with the dream of escaping from the stagnation of Japan, overlapping with the rebellion Fujikawa entrusted to Yamato. Thus, Masuda also played a role in the birth of Yamato by expressing his strong feelings about it.

Case 5

Hiroshi Miyagawa: Incorporating the best tradition of pop songs into Yamato

In addition to the visual world of Leiji Matsumoto, Space Battleship Yamato has another face: the music by Hiroshi Miyagawa. Regarding the theme song, Miyagawa said,

“It’s quite dramatic, like a popular song, but I’m quite confident in it, and I’m really happy about it now.”

(Quote from Yamato the Quickening video)

This impression is not limited to the theme song, it is one of the features the runs through the entire BGM of Yamato.

Miyagawa was well known at the time for his hit song Una Sera di Tokyo by The Peanuts, and was said to be their foster parent. [Translator’s note: The Peanuts were a female pop duo who also appeared as the singing fairies in Mothra.] He also appeared on the popular music TV program Geba Geba Geba and was known for scoring the film Irresponsible Japanese Bastard.

However, he is better known for his later work on Yamato. The music of Yamato is largely based on the sensibilities he developed in his flamboyant pop songs. Miyagawa composed the music for Yoshinobu Nishizaki’s Wansa-kun and continued into Yamato.

The music of Yamato is often described as a symphonic (and the sequels are to some extent), but that term is particularly misleading for “Part 1.” The famous Symphonic Suite Space Battleship Yamato is a collection of image music created after the broadcast, as opposed to sound sources used in the anime. The actual BGM score is composed of brass, violin, and other strings, woodwinds such as oboe and flute, piano, drum, electric guitar, and percussion.

It is clear from this that the Yamato Studio Orchestra (a name devised solely for the recordings), which was in charge of the BGM, was not a purely classical orchestra, but rather a popular orchestra (or pops orchestra). The music played by this orchestra is also, in the parlance of the time, light music (unlike rock music, it is easy listening pops with little rhythmic color), and is not a symphony in the exact sense of the word. Nishizaki called it a pops symphonic sound.

Miyagawa said, “Among all the songs I’ve written, The Infinite Universe is the one I like best of all.”

(Quote from Yamato the Quickening video)

This tune, with Kazuko Kawashima’s famous “aaaAAAH” scat is said to have been written in only two minutes after the idea came to him. (Listen here.)

(Symphonic Suite Yamato, liner notes).

This piece is centered around the scat, strings, and harp, but it is enriched by drum rhythm and hi-hat. The electric guitar and piano are partially used as accents. Overture, the opening track of Symphonic Suite, has the same motif but the strings sound is quite prominent. Although a drum is used, its sound recedes.

At the time, it was common for TV anime theme songs to be changed for brave or sad variations in the BGM. But in the case of Yamato, as seen in The Infinite Universe, the BGM is made up of many melodies composed separately. In particular, Miyagawa’s rich and beautiful melodies, combined with Kazuko Kawashima’s scat, had strong emotional appeal.

When the Yamato movie opened, Miyagawa commented that, “When we think of music for a science-fiction film, we tend to associate it with inorganic electronic music. But in this film, where the theme is the drama and love between human beings, I wanted to express the universe captured by the heart, pulsating with sadness and joy.

(Weekly Myojo magazine, August 21, 1977).

There is a certain excessiveness in the music of Miyagawa’s Yamato. If the BGM for TV anime at that time was simple, then film music could be said to have played a supporting role on the screen. Elsewhere in anime, the scores for Yoshiyuki Tomino’s Gundam and Ideon films has high quality (especially the latter), but the music clearly plays a supporting role. Even in the later films (sequels), the music is not as strong as in the earlier films.

Miyagawa’s music, which asserts a presence greater than that of a supporting character, became one of the features of Yamato. Its excessiveness lies in the assertive melodies and strong rhythms.

Yamato Bolero, used in Episode 15 and others, is a four-beat piece derived from the Latin bolero, which is used in dance. Before Japanese pops music was divided into enka (folk) and new music, there was a time when it had a variety of styles, incorporating jazz and Latin music. Ryoichi Hattori is a typical example.

Miyagawa was a writer who inherited a legacy from the best the old songbooks, and the abundance of his sources can be seen in the various ideas he came up with for each sequel. In Final Yamato, the scene of the enemy’s attack surprisingly uses a flamenco-like Spanish style. Exploration Boat, used when launching the Cosmo Zero, was composed mainly by a brass ensemble with electric guitar, drum rhythm, hi-hat, and Hammond organ as an accent. Miyagawa’s rhythm is well expressed in this tune with a good groove.

His BGM for battle scenes is composed of alternating brass and strings. This is the basic structure that heightens the sense of urgency. The original Yamato theme, used in rallying scenes throughout the series, also follows this basic form, and its interesting point is the use of electric guitar at the beginning of the song and in the rhythm part. (Listen here.)

In anime songs of the time, “plus” was used as the main part, and strings were used as accents in some parts. The mainstream method was to sing loudly. The main part of the Yamato theme uses brass as the main part and strings as the accent, but the main difference is the use of Kazuko Kawashima’s scat, electric guitar, and Latin percussion as hidden flavors. This light rhythm gives the song a pops flavor, rather than the heroic military-style anime song itself. This is in contrast to the vocal piece Space Battleship Yamato ’83, which was later arranged into a symphony march and sounds like a military song. This is the reason why Miyagawa described it as “pop song style.” The Scarlet Scarf in particular is exactly like a Showa-era song.

Miyagawa’s sense of melody, his diverse range of styles, and his sense of rhythm gave Yamato a breath of emotion, novelty, and dynamism.

In Episode 3, Yamato blows up a giant missile and flies away from the smoke. The song Yamato flying away from Earth is used in that scene, a light concerto of brass and strings. Electric guitar and Latin percussion were also used in some parts. Leiji Matsumoto insisted on the use of a symphony. It is said that objected to this arrangement with its electric guitar, calling it “troublesome.” (from the court documents mentioned earlier.)

But I think dynamic pops was the right decision. For the purpose of this story, which is to reconstruct old things with new values in a new era, the symbolic scene of Yamato‘s rebirth and flight needed youth and dynamism. In this sense, Miyagawa conveyed the core of Yamato through his music.

Case 6

Yamato‘s colors created from zero

At the time, there were paints specifically designed for anime, but Producer Yoshinobu Nishizaki was not bound by such industry norms.

Before digital coloring, cel anime was created by hand painting on a thin film of celluloid, which was then layered and photographed. Unlike canvas painting, where the artist mixes and paints the colors, anime is produced through a controlled process, and the number of paints used is pre-determined. The reason for this was to control costs by unifying and reducing the number of colors.

However, there was a downside. Looking at the anime of the time, it is clear that with fewer colors available, the color schemes emphasized simplicity and vividness. However, Nishizaki did not like this and ordered special paints to give Yamato‘s hull the texture of iron.

Its color has the weight of iron, but with a black tint. Nishizaki’s peers complained that Yamato‘s hull would blend in with the black of space, making it difficult to see. However, considering that real weapons often use a color scheme that makes them difficult for an enemy to spot, this approach is realistic and correct.

Leiji Matsumoto was also particular about colors. He instructed the color of the universe to be Sakura Matte Blue, an opaque watercolor. In other anime, poster color was used for backgrounds, but this paint contains white particles, so it looks bright even if the screen is black. Matsumoto wanted to prevent this. Compared to the typical anime universe, including Matsumoto’s other works, the colors are darker and more subdued.

Matsumoto also brought his own ideas to anime production. He painted stars in space backgrounds not by scattering droplets of paint from a brush by hand, but by clamping a brush to a water pipe and flicking paint against it. Since there was no hand movement involved, the paint droplets scattered in an even and natural manner. This was a result of his experience as a manga artist, not as an animation artist.

At this time, anime and manga were already differentiated, so, except for the form of original works, Matsumoto was the first manga artist to be fully involved with anime production since Osamu Tezuka. This was another departure from the industry norm at the time, but it actually worked well on the screen.

(Leiji Matsumoto, From the Far Place Where the Ring of Time is Linked, Tokyo Shoseki, 2002)

Ishiguro’s book TV Anime Frontline. Read the Yamato chapter here.

Art Director Hachiro Tsukima studied the color trends of Matsumoto’s works, and ordered and prepared the paints to match. The paints were less vivid than those used in other anime and had a more natural coloring (meaning low saturation), which helped to give the overall impression of warmth.

(Noboru Ishiguro and Noriko Kohara, TV Anime Frontline, Daiwa Shobo, 1980)

The color scheme of Space Battleship Yamato, as well as the paints, is less saturated than that of other anime. Unifying the colors, rather than being more vivid, created harmony on the screen. Comparing Space Battleship Yamato with other Matsumoto anime, you can see how wonderful it is.

A great deal of time and effort went into the process of creating the visuals. At that time, a 30-minute TV anime used an average of 3500 to 4000 cels. It was not unusual for Yamato to use 8,000 per episode, 60% more than the normal amount. Cels were also usually layered up to five sheets, but in some cases Yamato went up to seven.

Moreover, the complexity of Yamato itself, with its anti-aircraft guns and details everywhere, was far beyond the mecha of other anime at the time. Yoshikazu Yasuhiko, known as the animation director of Gundam, storyboarded most of the Yamato series. When asked if he drew any of the key animation, he replied:

“No, I’m glad I didn’t have to draw more. If I was also asked to draw animation, I would have run away immediately. I was thinking, ‘I don’t know who’s going to animate this, but thank you very much for your hard work.’ If we were talking about physical things alone, it would have been about four times the production capacity of the Gundam site.”

(Gundam Mono: The Men Who Made Gundam, Kodansha, 2002)

The sheer volume of work on Episode 22, Decisive Battle! The Battle of the Rainbow Star Cluster! has become legendary in the history of anime. Here, the Domel fleet’s fighters, dive bombers, and torpedo bombers are used. There is a battle scene in which Yamato‘s Cosmo Zero and Black Tiger squadrons respond to the attack. The precision of the scene was far beyond the level of the time. It is said that the nine key animators of Tiger Team Productions, including Takeshi Shirato, spent 50 days in the studio on this episode.

“It almost destroyed my company, Tiger Pro. I started working on Yamato because I wanted to do that big battle scene, so I put a lot of effort into it.”

(Yamato Perfect Manual 2, Tokuma Shoten, 1983)

Case 7

Movement, design, sound effects; everything was new

Movement was also a challenge unique to Space Battleship Yamato. The so-called “starfish explosion” was a depiction of flames spreading in all directions. This was created by Noboru Ishiguro, who also served as animation director. He later became known as the chief director of Macross and the general director of The Legend of the Galactic Heroes.

“I was fed up with the unscientific nature of robot anime, and when I heard that this was a full-fledged SF work with visuals by Leiji Matsumoto, I participated with high expectations. The starfish explosion was designed to create the effect of a sustained explosion, which is very powerful. At that time, space combat movies were almost nonexistent. It was a completely new spectacle, both in terms of how it was made and how it was viewed. Knowing that there are various ways of thinking about explosions in space, such as having them disappear instantly, we chose the power of the appearance. This starfish explosion became one of the formats for explosions in space.”

(Noboru Ishiguro and Noriko Kohara, TV Anime Frontline, Daiwa Shobo, 1980)

However, he did not use this format in his later works Macross and The Legend of the Galactic Heroes.

Ishiguro’s obsession was extraordinary. He didn’t just correct key animation, he also went as far as to fix finished cels. At that time, there were no full-scale SF works, so there weren’t many animators who could draw space battles with mecha to Ishiguro’s satisfaction. Near the end of the final episode, most of the mecha-related drawings were done by Ishiguro himself.

(Farewell to Yamato Fixed Data Materials Collection, Studio DNA, 2001)

In addition, an explosion scenes of a Gamilas fighter in Episode 22 was based on the actual explosion of a fighter plane in World War II. The scene in which the components fly apart was truly impressive.

Science-fiction itself was a new genre in Japan at that time, usually expressed only in novels and manga. The first SF anime is said to be Gatchaman by Rei Kosumi. Aritsune Toyota, who had participated in the planning of Yamato, was in charge of the SF concepts. As mentioned earlier, the idea of a radioactive Earth was his.

However, when it came to the stage of actually creating the story, Nishizaki did not like the “dry touch” characteristic of science-fiction, so many ideas and story plots were often rejected. Rather, it seems that many of Leiji Matsumoto’s ideas were incorporated. Toyota’s role seemed to be more about making things more scientific as they went along.

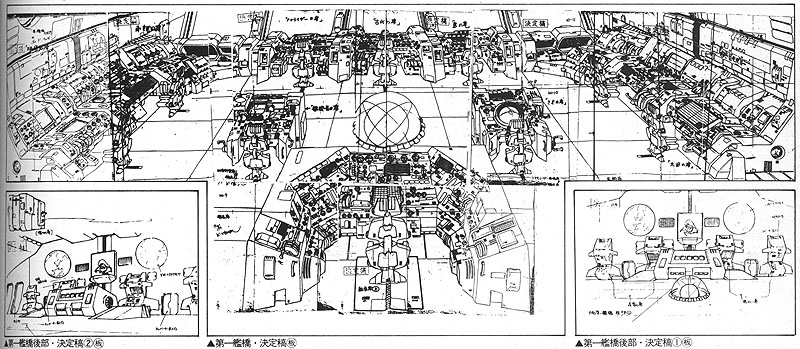

Matsumoto created the original ideas for mecha design, but the “cleanup” of the final draft was done by Studio Nue, a science-fiction design group, in a supporting role. Studio Nue had been involved in the project earlier than Matsumoto. This kind of planning group was unique at that time. Their presence was a sign of the maturity of the subculture market.

It was a followup to their earlier work on the anime Zerotester, but the workload was enormous. In that anime, they designed simplified model sheets to make animation easier to draw. Yamato had no such restrictions, so it was a true test of their skills. Later, it was feared that if they were allowed to get carried away, they would create impossible concepts. The term “yabuhebi” (bush snake) was modified to “yabunue” to describe them.

Noboru Ishiguro said, “What we drew [on other anime] is not what you saw on the screen. Animators would leave out details without permission because it would be too difficult to draw. In that regard, I liked Yamato because it was drawn exactly as it was designed. The animators were forced to do impossible things.”

(Noboru Ishiguro and Noriko Kohara, TV Anime Frontline, Daiwa Shobo, 1980)

At the planning stage of Gundam, Studio Nue proposed the original concept of mobile suits called powered suits. The reason they were not adopted was the huge amount of drawing work that would be required for their design.

(Gundam Mono: The Men Who Made Gundam, Kodansha, 2002)

Another important person to remember is Mitsuru Kashiwabara, who was in charge of sound effects. He brought Yamato‘s sound world to life with his vast and unique sounds.

Just as a small sampling, there was the sound inside the ship (air-conditioning?), interiors on the Gamilas side (different air-conditioning?), the rotation sound of the engine (tachyon particles are used, but there is a rotation mechanism), Wave-Motion Gun energy from filling to firing, the main gun firing sound (made from a turret turning to firing and trajectory extension), machine gun firing sounds (different sounds for different calibers), missile launch sounds (bow missiles and chimney missiles have different launch sounds), and grasping the control grips. The sound of Yamato in flight (although there is no sound in space) and the Gamilas ships in flight were also different. The sounds of the aircraft differed depending on the type, as well as the side.

Each mecha had a well-defined function, principle, and operating procedure. Kashiwabara’s sound effects supported such an elaborate world view. The Wave-Motion Gun was fired after a mind-boggling process, heightened by the sound effects, which gradually rose in pitch.

A scene that can be seen by the eye is called a landscape, whereas a scene heard by the ear is called a soundscape. The analog sound effects, which were not artificial sound effects created by synthesizers, together with Hiroshi Miyagawa’s emotional music, brought a fully flesh-and-blood soundscape to Yamato.

In the movie Resurrection, the sound of the main guns firing was different, and there were quite a few claims that it seemed trivial to the casual observer (prompting a complete remix for the Director’s Cut). This is how much the fans responded to the staff’s attention to detail.

Case 8

The “warship march” incident; a misinterpretation of the work

Although Space Battleship Yamato is the culmination of the thoughts, ideas, and efforts of various staff members, there were some discrepancies over the interpretation of the world.

Toshio Masuda, who insisted on realism, seemed to be a bit more conscious of the film as a fictional war story or war movie. If you insist on realism, you have no choice but to depict battles in a harsh manner. Yoshinobu Nishizaki was somewhat similar.

Compared to Nishizaki and Masuda, Leiji Matsumoto’s ideas were more like fantasy, a great voyage of the universe. In the World War II flashback scene, he gave instructions not to depict the rising sun flag (used by the former Japanese Navy). Yamato‘s crew was not divided into departments like the Battleship Yamato, but into groups. The salute is not military style, but rather a unique one with the arm raised to the chest.

None of the above is military style. Yamato was a reflection of Matsumoto’s desire to eliminate military overtones as much as possible. Noboru Ishiguro agreed with Matsumoto’s stance of “creating a style that is not biased to the left or to the right.” This intention of Matsumoto’s became a plus in the worldview. This is one of the reasons Matsumoto’s works have been supported by so many people.

On the other hand, Keisuke Fujikawa says he aimed for neither realism nor fantasy, but something in between. However, it seems that the staff’s disagreement over the work was not decisive, at least in “Part 1.”

In Episode 2, The opening gun! Space Battleship Yamato start!! the scene where the battleship Yamato was sunk by the U.S. forces during World War II appears in a flashback. Nishizaki wanted to use the Imperial Navy Warship March theme for the scene of the Yamato advancing. Matsumoto was adamantly opposed.

Seeing Nishizaki’s refusal to back down, Matsumoto even considered quitting the program. However, at a production meeting, Assistant Director Susumu Ishizaki said,

“I have a question. I heard that the Warship March is included in the second episode. What is your intention in using it? We don’t want to help you create a right-wing work. Depending on your answer, we may have to quit right here and now.”

(Noboru Ishiguro and Noriko Kohara, TV Anime Frontline, Daiwa Shobo, 1980)

In the end, the Warship March was not used in the film. The scene was replaced at the last minute with a redubbed tape instead of the print that had already been delivered. However, the Niigata region didn’t receive it in time, and the episode was aired with the Warship March. Since the original film was not modified, the Warship March was heard in reruns. Incidentally, the movie version does not include it.

Yamato was made by creators with their own ideas, values, and sensibilities, and this was reflected in the work. If even one of the main staff members was missing, Yamato as we know it today would not have been created, and may not have been supported by the public.

It is hard to imagine, for example, if Yoshinobu Nishizaki, Leiji Matsumoto, or Hiroshi Miyagawa had not been there. Therefore, I think that the resulting works are not the expression of a single person, but the product of a collective consciousness.

The anti-modern as a criticism of civilization, questioning the postwar period, nostalgia for the past, desire to escape to outer space, tremendous enthusiasm and a sense of freshness all contributed to an unprecedented expression in the emerging genre of anime. The fusion of these various elements in a delicate balance gave birth to Yamato.

It may have been a strange coincidence of the times.

NEXT CHAPTER: The Most Important Lessons of Yamato

For further reading: all of the story proposals mentioned in this chapter have been translated in full and can be read in the Yamato Origins series, starting here.