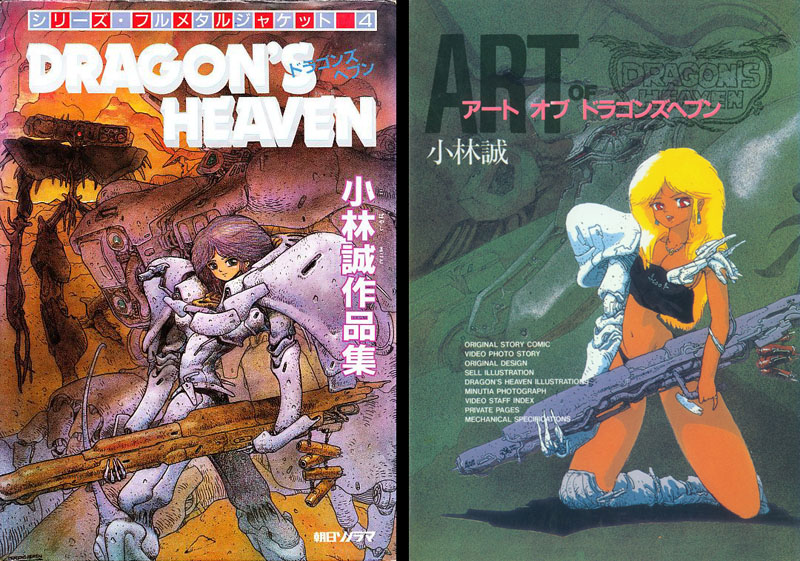

Few people have enjoyed careers like Makoto Kobayashi’s. Born at exactly the right time to enter the world of anime at its explosive peak, he walked in with a skill set that gave him maximum versatility: writing, publishing, manga drawing, professional-grade model building, mecha design, and most importantly the ability to orchestrate all of them simultaneously. As a result, he rose quickly through the ranks to create and direct his own title (Dragon’s Heaven) in 1988 and has remained at the top of his game ever since.

He has also enjoyed a unique Space Battleship Yamato career, having been a major participant in the new projects of the late 80s/early 90s. He then returned to get Yamato Resurrection over the finish line and take the lead on the 2012 Director’s Cut of the film. We interviewed Mr. Kobayashi during the week of its premiere and now share with you the stories only he can tell.

Interview conducted February 2, 2012 by Tim Eldred and Sword Takeda.

History and Development

When did you first see Space Battleship Yamato?

When it was first broadcast in 1974. I was a 16-year-old freshman in high school. The anime Samurai Giants was broadcast before Yamato in the same time slot and was cancelled, so I had great interest in what kind of program would come after it. I wanted to know what kind of anime would replace my favorite. When I saw the first episode, I was shocked by how wonderful it was.

Were you a fan of anime and manga before Yamato?

I had all the favorites of a normal child, manga magazines, plamo [plastic models] and SF novels. I started building plamo when I was 5 years old.

How did you become a professional plamo builder?

I built models as a means of understanding mecha design. I also created stories and published doujinshi [fanzines]. I sent them to different publishing companies and later received two offers. One was to do an original photo story in the Kadokawa movie magazine Variety in December 1982. The work included story and design.

Another offer came from Bandai in 1983, and I also started work on story and design for the first two volumes of Hyperweapon. That was my first job as a pro modeler.

Hyperweapon [Future Super Weapon] volumes 1 and 2, specials published by Model Art magazine in 1984;

a dystopian SF story told through model photography, designed and produced by Kobayashi. He continues to create

Hyperweapon in cooperation with Model Art as a showcase for his many projects. (Shown at the end of this page)

How did you become a professional mecha designer?

Yoshinori Kanada saw my doujinshi and asked me to do mecha design for his original plan for Birth (1984). [Editor’s note: Kobayashi also designed mecha for the high-profile TV series Mobile Suit Zeta Gundam in 1985 and its followup, Double Zeta in 1986.]

How did you become a professional manga creator?

It started when the chief editor of Model Graphix magazine was in a hurry and asked me for a short story manga. That’s when I started Dragon’s Heaven.

Was there ever a time when you worked as a mangaka, modeler, and mecha designer all at once?

Yes, on City in Labyrinth. [Editor’s note: this was a late-80s multi-media project with articles in several magazines.]

How did you move from mecha design to directing anime?

I was directed to create an original story, and I was asked to direct the Dragon’s Heaven anime. The manga was done in a hurry, but it got a very good reputation and became an anime. I appreciated the wonderful work of the animators and all the others. It was a happy ending to the story, but nothing else happened with it afterward.

Your work shows influences that do not seem to come from Japan. Are there foreign works or artists who inspired you?

In Dragon’s Heaven, I think it is unmistakable. It was influenced by the work of Jean (Moebius) Giraud, but I was not necessarily influenced by anyone in the area of design.

Space Battleship Yamato: Round 1

How did you become involved in Yamato projects?

It started in 1986 when I got a call from Mr. Nishizaki’s office. I was recommended by Sunrise.

I’d like to ask you about a Yamato project that did not get finished, called Dessler’s War. Could you talk about your experience with that?

What do you know about it?

It was reported in the Yamato fan club magazine. Mr. Nishizaki described two or three versions of the story, and then many years later the only other thing we saw was your design for Battleship Starsha. Can you talk about the creation of that art?

Mr. Nishizaki told me why Dessler decided to build Battleship Starsha. I was given a rough description. Dessler’s hope was to get a stronger battleship, but in the end the result was something like Starsha’s face. I was asked to design that. When I brought it to Mr. Nishizaki, he told me one or two story ideas. For each plot, many other designers had a presentation.

In Mr. Nishizaki’s mind, the plot or the music came first, then some pictures were developed to fit into them. That was his way of thinking. But after he saw the drawings and paintings, he thought he wouldn’t get enough support from the audience.

What year was that art made?

Between 1986 and 1988. The idea of a remake was first proposed at that time, and I was asked to draw for it, then the next title to come up was Dessler’s War. In 1987 the plan for Resurrection began, using the 2520 Yamato designed by Syd Mead.

Mr. Nishizaki said that with this new shape and design, Yamato Resurrection would be possible. Then I thought, usually he begins with music or a plot, but this was the first time to begin with visuals. So my memory of this is vivid and precise.

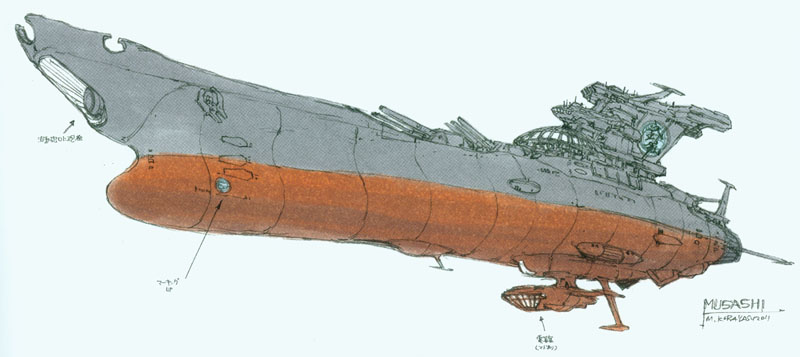

The problem was that Syd Mead’s cross-section of the ship did not perfectly match the outline of it on the image boards. In other words, each image showed a different shape, so I worked to make a three-dimensional version from that. From his key design, I produced a huge amount of production design to be used for the film.

In the 1994 Yamato documentary The Quickening, we see a large model of the 2520 Yamato. Did you build it?

Yes. It is now on display at the Cafe Crew restaurant in Aoyama.

You were heavily involved in pre-production on both Yamato 2520 and Yamato Resurrection. What do you remember about working on them at the time?

On Resurrection, we were keenly aware of the weight of the work. On Yamato 2520, I learned the means of building production design from key design.

What was it like to work for Mr. Nishizaki during that time?

I felt that he was an excellent conductor.

Many times during the 1980s, he wrote that it was difficult to create the next Yamato story. In the fan club magazine, he said that he kept changing the story to find one that he liked. Then in 1993, it seemed like Resurrection came from nowhere, very quickly. Is that the way it actually happened?

I can only guess, because I did not hear the story directly, so this is just my point of view.

In previous stories, the question was always, what will Yamato do next? What kind of crisis would come up? What kind of victory would Yamato have, and what would be the impression of the audience? That sort of logic. This was a tough task. Not just anyone could handle it.

However, in the case of Resurrection, the revival of Yamato would be the main story point, unlike the previous ones. Once Mr. Nishizaki decided if Yamato would revive or not, it was very easy to make the story from there. Therefore, in 1993 setting the framework of the story was an easy task.

Deciding the ending was the most important. At that time, three things were settled on: we would see the barren lands of Africa, Yamato could not save the Earth, and then part 1 would end. That’s when it was introduced to me. As of that moment in 1993, the Syd Mead Yamato was shifted over to 2520 and the classically-shape vessel came back.

Was the script already finished when you joined the production?

No, it was still being written.

Did you have any influence on the script?

Yes, in the 1993 version there was a much longer story about the Amare solar system. I suggested that it be shortened.

In the 1994 Documentary, there was a model you built in the Resurrection style that had some interesting features. The bulge on the foredeck was designed to separate and become another spacecraft with the ECI inside, but this plan was changed. Why was that?

It was due to a change in the character of Kosaku Omura. Originally, Omura was to be two separate characters, but they were merged into one. One of those two had accompanied Kodai for a long time, and the other was to perform the suicide attack. That character was similar to Maho Orihara, who works in the Information Processing Center, so the ECI room needed to be equipped with a separation mechanism for the attack.

But it was decided that Omura would perform the suicide attack rather than the Maho-like character, so there was no need for the ECI to separate. That’s how it came about.

Also on that model, the side panels opened to reveal smaller ships. There was a DX Yamato toy made by Popy in 1980 with this same feature. Were those two ideas connected?

No, it was just a coincidence.

Then, did the smaller ships become the Shinano?

It was an entirely different thing, with a different role. In 1993, the reason for the extra ships was to add two or three more engines to Yamato, which was an idea of Mr. Nishizaki.

Their names were Seiran and Kouriyu. Seiran was a ship that broke a speed record using the wave-motion engine, and Kouriyu was the Earth’s first space submarine. Both were to be equipped with powerful wave-motion engines. By incorporating these two ships into Yamato‘s six-core wave-motion gun, there would be a total of 8 cores and in this state the transition wave-motion gun could be fired.

At the time, Mr. Nishizaki devoted himself considerably to the concept of transition energy, and for the 2520 version, he was thinking of the wave-engine as the sub-engine to another called a monopole engine. The generation of energy changed.

After your work on Yamato in the 1990s, what path did your career take?

I did anime that was similar to Yamato, such as Giant Robo, Sin, and Super Atragon. My other projects were Steam Boy, Final Fantasy Unlimited, Gravion, Last Exile, Samurai 7, Gankutsuo, Brave Story, and Doluaga. I also published a magazine called Model Car Racers and worked on the games Bertorger 9 and Lost Odyssey.

What was different about the industry during these years compared to your earlier years?

The anime industry was always changing, but going digital was the point of greatest change.

Space Battleship Yamato: Round 2

How did you become involved in Yamato again?

I was asked by Mr. Nishizaki over the phone. No matter what the plan was, I wanted it to appeal to more people.

What tasks did you perform on the 2009 version of Resurrection?

Mecha design, early image boards, some art designs, some special effects, some storyboards, and assistant director.

What did you do as assistant director?

Literally, it means that I assisted the director. If you’ve had experience making a movie, you understand that directing is not a position or a post, it’s an activity. The assistant director or sub-director takes care of tasks that require support and go beyond the work of a director.

There’s a new character in Resurrection named Kobayashi. Was he named after you?

The name already existed in 1993. I asked the scriptwriter about it, but he said no. It was thought up by Mr. Nishizaki and the scriptwriter, and was not related to me.

What was it like working on Resurrection the second time around?

In the case of my designs, if I came up with some vague auto-gravity-like thing, it would never be adapted. It is always subjected to supervision. In the 80s it was different, but that sort of free spirit doesn’t work now. Very detailed calculations are applied even if the idea is just made up. Everything is carefully designed to support the understanding of the story. That’s why the designs follow this shape.

The mecha design for Resurrection seems to point the way to 2520. Was this a specific goal?

That was the wish of the director.

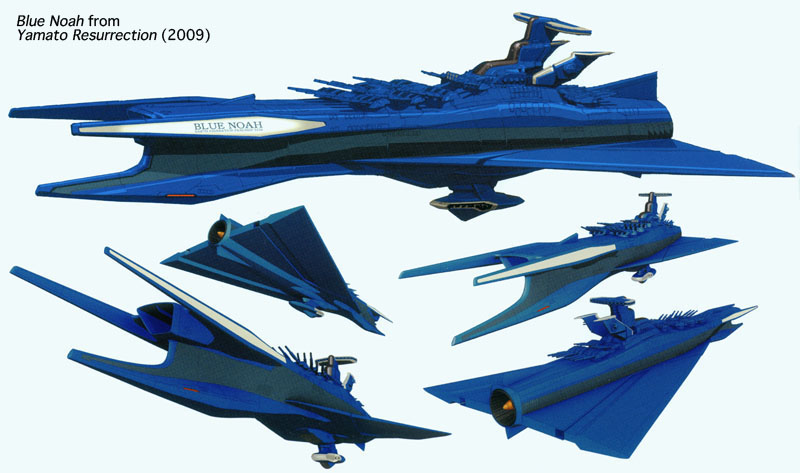

How was it decided to use the Blue Noah from 2520?

The ship has the same name, but the design is different. It is retroactively designed as the ancestor of the Blue Noah in 2520.

In the 2520 version, the ship is equipped with a lower gun turret, which we removed. The Resurrection version is similar to Yamato in that there is a waterline and since the underside is not considered a combat zone, the turrets only point up. Even down to the millimeter level, it differs significantly.

The large SUS battleship seems to be a dimensional ship that emerges from a separate dimension and sinks back in. Is that the same effect we saw in Yamato III?

The subspace ships in Yamato III make splashing waves when they come up. When they emerge from the other dimension, they make an image like an ocean or the sea surface. Strictly speaking it isn’t an effect, it is a computer-generated “sea.” It was inspired by a submarine.

The tower of the giant SUS fortress looks like it’s sitting in water. Is that the same kind of subspace dimension? Is the tower like the tip of an iceberg?

Yes. In another scene, Metsler and Barlsman of the SUS are holding a meeting, and the location is not somewhere else, but connected to the same vessel. It is another location inside the same huge fortress.

You have created some new Yamato mecha, as seen in Hyperweapon magazine. Will they be part of future stories?

That was done specifically for the Director’s Cut.

In the movie there are many members of the original crew, but there are some that we don’t see. Do you know why we didn’t see other characters, such as Nanbu or Aihara?

Mr. Nishizaki never put them in the script. The original version of Resurrection was almost two and a half hours without them. If they appeared in it, it might have been four or five hours long. From my point of view, in the Yamato world they could be in different ships.

What are your fondest memories of working on the movie?

My best memory was to help the director achieve his aesthetic sense in the production.

When it was revealed that Resurrection was part 1 of a new story, everyone wanted to know when part 2 will be made. What are the necessary conditions for that to happen?

Everything depends on the support of the audience.

Space Battleship Yamato: Round 3

It’s quite unusual in anime to see a Director’s Cut. Could you talk about the decision to make it?

Mr. Nishizaki was the one who decided to make the Director’s Cut. I want to strongly emphasize that the director was Mr. Nishizaki. If he didn’t intend it, there would be no such film.

Did he have the idea for it before or after the release of the 2009 version?

The one he intended was the one released in 2009. Later, he decided to do it again under the name “Director’s Cut.” It is customary for the director to perform the edit on a movie. So if he had wanted to make the Director’s Cut before 2009, it would naturally have come to fruition in 2009.

In the sense of packaging, usually a Director’s Cut means many deleted scenes will be restored as a business strategy. From the filmmaker’s point of view, it’s not actually a director’s cut, it’s “another new cutting,” or an alternate version. Therefore, it had to come after the 2009 version.

What was the status of the production when Mr. Nishizaki died?

At that stage, the animation director Nobuyoshi Habara and I weren’t participating at all. There was a finished blueprint for the production, but the actual people who would do the work hadn’t been decided upon. There were many options, so Mr. Habara and I narrowed down the possibilities, completing the plan after matching it up to the words of Mr. Nishizaki when he was alive. So it’s reasonable to say that before Mr. Habara and I participated, the production could not have materialized.

The biggest difference, of course, is the sound and the music, both a great improvement over the original version.

In my opinion, it was the editing. The story flow is smoother, so other elements can be heard much more vividly. I’m not dismissing the original 2009 version, but if the cutting technique is different, it must have an impression similar to a Director’s Cut.

The music and sound effects plan for the Director’s Cut was devised by Mr. Nishizaki. Music materials had already been recorded when we started working on it. The only part I directed was when Yamato launched; which music should be used? I remembered that Mr. Nishizaki couldn’t decide which was better, with vocals or without. So I decided that this time we would go without.

In the case of sound effects, we proposed a plan and Mr. Yoshida worked hard to realize it. I don’t know the situation in America, but in Japan the sound designer doesn’t tell a subordinate or a successor anything. The son of Yamato‘s original sound man, Mitsuru Kashiwabara, didn’t know anything about the legacy of those sound effects, so we initially declined to use them [in the 2009 version].

Mr. Yoshida tried many ways to get in touch with Mr. Kashiwabara. In the last stage of recording, he actually attended a sound mix and he said, “I don’t know anything about how young people do it now, but this particular part should be more like that.” So that direction actually happened.

In a 2009 interview, Mr. Nishizaki felt very strongly about using classical music as part of the score, and of course now in the Director’s Cut most of the that music has been replaced. Do you know why he made that change?

I’m not him, so I’m not sure, but he always wanted to make new music. He was a kind of musician, so music came to his mind first, and other ideas would follow. When I was called in, he had already told the music supervisor the general plan.

You had the unique opportunity to work with Mr. Nishizaki in 1993 and then again for the 2009 movie. And we know that between those two times, many important things happened in his life. Can you describe what he was like in 1993, compared to 2009?

There was no difference.

Did he have as much energy as an older man as he had as a younger man?

Yes, quite the same.

Do you think there is anyone else like Mr. Nishizaki in the anime industry now? He seemed very unique and unusual for a Japanese man.

He was a producer, first and foremost. That’s exactly what a producer is like. Other producers are not like him in some ways, not showing things openly the way he did.

Mr. Nishizaki didn’t mind public speaking, and he would brag openly. In fact, in 1993, I thought Mr. Nishizaki was the only producer with those negative aspects. Later I learned that all producers had them, but they kept them hidden. Since he revealed them openly up front, there were exaggerated rumors about him, but it was actually his way of expressing kindness.

I have made many anime other than Yamato, and had a very hard time on them since the problems were not revealed up front. Then I remembered that Mr. Nishizaki always revealed problems at the beginning, which showed he was quite fair. So when I teamed up with him again for the 2009 version, I felt he was a frank, open-minded, honest producer as well as a director who did not hesitate to address the anxiety and worry that others don’t even mention.

The staff would be confused, but if you paid close attention, you could see that it was just him being indecisive. Other directors and producers would bring up problems later when time is running out, and that also confuses a staff. In the days of Yamato 2520 in 1993, the staff only saw it as Nishizaki’s bad nature, trying to protest against his uniqueness altogether. But looking back on it, I think every director has a moment of indecisiveness, and there is always conflict. But once decided, there is no hesitation to move forward.

In Mr. Nishizaki’s case, he revealed to everyone around him what others would keep hidden and said, “what about it?” But he was trying to make it clear, to distinguish between wanting helpful ideas on some things while definitely wanting others not to be touched. It was a kind of organizing process. But those around him at least tended to be collaborators.

As a director myself, I understood him quite well, guessing he wanted to give his best performance in this framework. Then my thoughts were about not repeating bad situations again. When other producers would bring up problems very late, I once gritted my teeth so tight that my back tooth actually broke. He didn’t deserve that. So all I could do for him was to let him be indecisive on particular matters as long as he wanted, while he left other matters to me.

I suggested a realistic schedule that would actually work, as well as methods and ways that worked. I gave him general “we will go this far in this period” type of plans.

He first tried to visualize the black hole as animation cels, but it was completely impossible, so I suggested alternate ideas. The impossible becomes possible when you work on it from the beginning, not the middle or the end. So our interactions were quite smooth, even over the phone.

In this way, Mr. Nishizaki was not the man people perceived. Not a hard man to understand, or just a strange guy.

On the premiere day in 2009, Resurrection played at major theaters, and the Director’s Cut is now playing in a much smaller theater, the Cinemart. Was there ever the possibility that it might go back to a larger theater chain?

Distribution here in Japan is really small. The title came into the peoples’ minds first: “Yamato Resurrection? Didn’t we see that already?” The same thing happened with Blade Runner here.

There were about 20 years between the two versions of Blade Runner. It was a failure when it was first released, but then it became a classic as the years went on. Many more people knew about it when the “Final Cut” came out.

With the Director’s Cut of Resurrection, it had been only two years since the original version.

Maybe in another 20 years there can be a “Final Cut” for Resurrection.

(Laughs) That might be possible!

In your opinion, what would be your perfect Yamato movie?

From my point of view, the 2009 Resurrection and the Director’s Cut were both perfect. But the 2009 version had a stronger sense of telling a story to people who didn’t yet know about Yamato. That is the spirit of Mr. Nishizaki.

The point now is to tell the story again to the audience who already knows Yamato, the longtime fans. In both cases, the spirit is there, and it’s perfect. The Director’s Cut embodies the enthusiasm of Mr. Nishizaki, and I took into consideration his feelings of wanting to create maximum appeal for the traditional fans. But the fundamental content is the same.

What was your impression of the live-action Yamato movie?

I think the director, Mr. Yamazaki, had a very difficult job and did it very well.

What are your goals over the next ten years?

I don’t plan that far ahead. I can’t answer that because I just can’t imagine the next ten years.

What’s your next project after this one?

I can’t talk about it at present, but I will when the time comes.

The End

Related links:

The Art of Makoto Kobayashi tribute site

Kobayashi’s profile on Anime News Network

A Partial Bibliography

Two Factory: The World of Makoto Kobayashi / Kow Yokoyama (Bandai B-Club Special #18, 1988),

The Art of City in Labyrinth (Japan Publishing, 1988), Model Car Racers #16 (Makoto Kobayashi Office, 1998)

Above and below: the complete run of Hyperweapon magazine as of early 2012, published by Model Art.

In Kobayashi’s words, new volumes come out “Whenever I feel like it.”

Thank you a lot for interviewing this truly awesome modeler. I had no idea his main work became anime direction. I would love to know more about his involvement with know Yokoyama. Makoto’s dorvasck document is ultimate.

Awesome article and interview…at 51, i still dwell in this incredible world of Yamato!