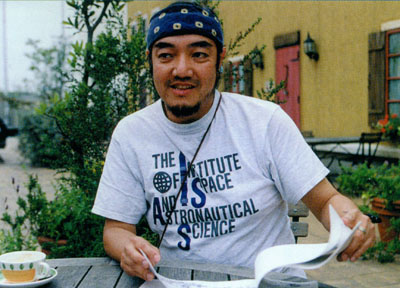

Master Mecha Designer Kazutaka Miyatake

Born in the port city of Yokosuka in 1949, Miyatake was fascinated with aircraft carriers and destroyers as a child, and this lead to a lifelong interest in mechanical design. He was a founding member of Japan’s Studio Nue and his list of credits includes some of the greatest anime programs ever created, such as Space Battleship Yamato, Superdimensional Space Fortress Macross, Space Pirate Captain Harlock, Brave Raideen, Super Electronic Robot Combattler V, Aura Battler Dunbine, Super-Robo Zanbot 3, and many more.

This interview with Miyatake was published in the liner notes of Bandai’s Yamato 2 Laserdisc box set in 1992. Though he did not work directly on the series, he was the primary mecha designer on Farewell to Yamato, and all of his work was preserved for Yamato 2.

Translation by Michiko Ito, edited by Tim Eldred.

You have been involved in the Yamato series from the beginning, correct?

Studio Nue was fully engaged in series 1. It consisted of myself and two other artists, Kenichi Matsuzaki and Naoyuki Katoh. Personally, I didn’t do much, about a quarter of the total. Matsuzaki worked hard, staying in the studio all the time. He did most of the job. Katoh was in charge of the Gamilas side. Then, in Farewell to Yamato, Matsuzaki moved to script and planning, so he did not draw. Katoh’s main job became illustration. So I took over design, since it was my specialty.

The mechanical designs in Farewell to Yamato look very sharp.

That’s due to the technique of the artists who interpreted Mr. Matsumoto’s rough mechanical designs. It’s a visual language, so to speak. Every artist has their own interpretation, I could say.

Mr. Matsumoto’s overall influence on the Yamato mechanical designs is quite strong.

Yes, and my job was to catch the ball after he threw it. We could add our own touches to some extent, but not completely. Every design goes through the “Matsumoto filter” to give it some uniqueness. Even though they are mere mechanical objects, they are also characters which compose the world of Yamato. I am not sure if I understood that in those days. But now I understand this is what design is all about.

An important part of our job was to create new designs using the essence of Mr. Matsumoto’s approach. I remember that later, he said the mecha design in Farewell to Yamato lay somewhere between Studio Nue’s style and his. He also said this was the result of our collaberation. Since he started out as a comic artist, he didn’t know how other artists would interpret his designs, but when he finally grasped the entire process, he seemed quite moved.

Was the first rough design of every spaceship typically drawn by Mr. Matsumoto?

Sometimes. Other times, we created the first rough sketch and he revised it. This was usually the way we worked.

The mechanical design for the Comet Empire side was very unique.

We had several design concepts for the Comet Empire. First, the images of insects or crustaceans. It was the Devastator that Mr. Matsumoto first created out of this concept–the one that looks like a horseshoe crab. Then he wanted to add parts that looked like the eyes of insects. In order to preserve the image of a crustacean, each panel was clearly drawn and joints overlapped like armor. Other designs followed this lead.

As for other Comet Empire fighters, Mr. Matsumoto came up with the design of the Itar II and the Paranoia, since he liked aircraft. I did cleanup only.

I designed the EDF Destroyer first. Looking at this, Mr. Matsumoto said, “Ah, this is where we’re going,” Then we proceeded to other mecha. Every time I presented my rough design, Mr. Matsumoto gave me his comments, such as doubling this element, switching front and back, putting two heads on that, etc. This is how the designs evolved.

As for the big battleships and the super-dreadnought, Mr. Matsumoto sent us many drawings. They were usually spread over four pages, like he had to keep drawing by adding pages one after another. It was the same when he designed Yamato. We often did this whenever we needed to draw big things. If we tried to keep a detailed drawing within a standard sheet of paper, the design looked shrunken. Larger drawings were easier to visualize and understand. We realized a big design on a single sheet of paper didn’t look big, so we resolved that it would be OK to exceed the limit. A real battleship is pretty big, after all.

But the problem in those days was, there was no copy machine that could reduce from the large size. Machines that could copy fine detail were very rare. Solid blacks wouldn’t copy well, either. I think it was during Series 1 when copy machines only became capable of copying solid blacks even marginally well.

Anyway, the production staff shrieked when they saw our four-page drawings, and we had to somehow shrink them back down to a single page, so we had to buy a tracing machine. I think it was quite an expensive item in those days. Using this machine, we shrank the image onto B-4 size paper. So you can imagine how the advancement of photocopying technology made a great contribution to animation production. In those days, we could only do designs that we knew would reproduce on the old machines. Now almost anything goes.

Also, lots of designs required lots of paper, and If we used a lot, the animators didn’t want to flip through them all. So, in order to decrease the quantity, we put as many pictures on a single sheet as possible.

What did you have in mind when you designed the Earth mecha?

The Andromeda was created as a Yamato-size ship. But it was supposed to be an entirely new design, not modelled after Yamato, so we had to create the ship with this understanding. I designed its basic, overall style. I also invented the twin wave-motion guns. Based on my design, Mr. Matsumoto revised the bridge to add his own touch. I cleaned up his revised design. This was the basic process for everything.

My personal favorite was the escort vessel. The shape is simple, and I designed other ships based on this. For example, two engine parts were added for the cruiser. I remember that for the main battleship, I designed something like a pistol attached to its bow. It looked just like a pistol if a grip were added at the middle of the hull. That was the image. All the basic designs were mine, enhanced by Mr. Matsumoto’s taste.

Did you design any non-mechanical things such as the main body of the White Comet?

Mr. Matsumoto designed the White Comet and the staff in the art division cleaned it up. To tell you the truth, the design is a common science-fiction motif, one of the ideas accumulated during the long history of SF. An American writer, James Blish, wrote a story titled Cities in Flight, which features the flying city of New York. That was one of the inspirations for the design of the White Comet.

A lot of the ideas in overseas SF works were attractive to us, but now we see that ideas originated in Japanese anime are often used there. I don’t know how many times the ideas in Yamato have been used in Star Wars and Star Trek. When we saw Top Gun‘s dogfight scenes, with the same timing and number of cuts as in Macross, we were astonished. Later, the director of the film said the scene was based on a Japanese anime, and credited us. This is an issue of great pride for artists.

As for the details of the White Comet, I designed the anti-aircraft cannon. Mr. Ishiguro did the first rough design. He also liked designing mechanics, so he often drew rough sketches. We put a lot of passion into the dogfight scenes between his anti-aircraft cannon and the Cosmo Tigers.

Were all the design specs decided by you and Mr. Matsumoto?

Yes. We determined the scale by comparing everything with the Yamato. By the way, the size of Yamato changed during the series. At the beginning, we calculated the length longer than 300 meters, judging from the size of the bridge. Mr. Matsumoto and Mr. Ishiguro agreed on this. But in published promotional materials, the length was given as 283 meters, the same as the original Battleship Yamato. Now that size is the official one.

The wealth of detail in your designs was quite unusual in those days.

Not many artists could design mecha at that time, so we went through a lot of growing pains. At the time, Toei asked us to draw plans of the mecha, and we were surprised by that. What a tough request! Each one took about three days. For us it was like doing an isometric drawing of a car or an airplane, from three angles. It really takes time. But the person who requested it looked at it and said “I don’t understand this.” Maybe he just wanted a simple diagram of the front, back and side.

Things have changed a lot since then. Now, anime artists regularly create designs that make us think “how could they draw such a thing?” Now we even have animators who specialize in mecha. Moreover, if the original drawing is rough, the animators can refine it and add detail. Expecting this, the designers just write in “please add details to this.” In the old days, animators complained if we didn’t put in all the detail for them. But in terms of the presentation of mecha, I think maybe Yamato changed the standards.

With regard to real science, we made every effort to keep the sense of zero gravity in space in Series 1. For example, it was a struggle to make people understand that explosions would not drop downward in space. Mr. Ishiguro did his best to revise drawings to convey this.

What place does Yamato occupy in you?

I studied a lot to develop my career. More than anything else, through this work I understood what it meant to collaberate with others. Yamato was an important step I had to go through to develop my career. Nothing else has been more important. If I hadn’t gotten involved in Yamato, I would’ve end up as an animator who could draw only robots. Maybe I wouldn’t even be a mecha designer anymore.

Also, Japanese SF anime and robot anime become almost synonymous, but Yamato exists as another option, and I find this very encouraging. In the future, when we present new concepts, some of them may be possible only because we have such a great forerunner in Yamato. When we want to bring our dreams to life with the act of creation, the success of Yamato gives me great inspiration.

The End

Read a 2001 interview with Miyatake here